Managing antimicrobial resistance requires action from the entire healthcare system; however, the main responsibility lies with medical microbiologists and virologists. Natasha Ratnaraja, Danny Scarsbrook and Angharad Davies ask how pathologists can win the fight against antimicrobial resistance in the face of significant workforce pressures.

In July 2023, the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) published its Three-Year Strategic Plan 2023–2026.1 The report described 3 overarching goals – Repair, Respond and Build – each with 2 strategic priorities. One of the strategic priorities within Respond is ‘reduce the impact of infectious diseases (ID) and antimicrobial resistance (AMR)’. Infection specialists will surely welcome the recognition of the importance of managing infections safely and promptly through robust surveillance, prompt diagnosis and good antimicrobial stewardship (AMS).

The antimicrobial stewardship workforce

However, this goal is not without its challenges. While AMS is, of course, the remit of all healthcare professionals, within secondary care, a large part of the responsibility tends to lie with medical microbiologists, usually working closely with pharmacy colleagues. They develop antimicrobial prescribing guidelines, using local resistance data and current literature. The UKSHA’s surveillance systems also rely on the involvement of medical microbiologists, virologists and infection prevention and control clinicians.

All these systems need to be delivered in conjunction with laboratory and diagnostic duties, providing an advice service and undertaking ward rounds of clinical areas such as critical care. The College has produced a position statement on AMR in the UK, outlining what the profession needs to be able to address this issue successfully.

The joint British Infection Association (BIA) and Royal College of Pathologists (RCPath) 2021 National Workforce Survey demonstrated that 17.5% (119 of 587.1) of all funded full-time equivalent (FTE) infection consultant posts (including medical microbiology, medical virology, and ID) were vacant.2,3 The highest proportion of vacancies (20.3%) were in medical microbiology, with infectious diseases at 9.3% and medical virology at 14.6%. This raises the question: how do we meet the challenge of reducing the impact of ID and AMR within the context of significant workforce shortages in the infection specialties?

The roles of the medical microbiologist and medical virologist

Workforce and services

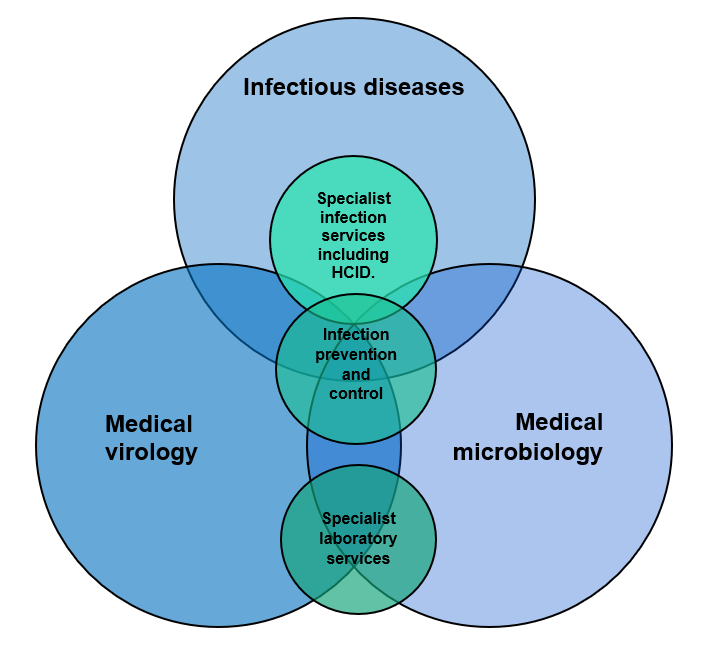

Within the infection specialties, there may be considerable overlap of duties. Infection prevention and control is within the remit of medical microbiology, medical virology and ID. However, in many trusts, there are no ID services; indeed, the BIA/RCPath workforce survey reported that, of the 108 organisation respondents to their UK workforce survey, only 54 (50%) reported having at least 1 infectious disease accredited consultant, mostly concentrated in centres within urban areas.3 Only 10 respondent organisations reported having an acute ID on-call take. Of the 704.6 FTE posts, only 39 FTE posts were single-accredited virology and 11.4 FTE posts were dual-accreditation ID and virology.

Thus, it can be assumed that, in most organisations, out-of-hours infection advice is provided by medical microbiologists. This would include infection prevention and control advice in many trusts. There is, however, considerable overlap between medical microbiology, medical virology and ID, with all specialties being involved in infection prevention and control and high-consequence ID units (where available), as well as specialist infection services. This is illustrated in Figure 1.4

Clinical role

Increasingly, medical microbiologists and virologists have been taking on more patient-facing roles. These include:

- in-person ward rounds on critical care and other wards

- seeing patients on ward consultations and referrals

- assessing and reviewing patients for/on outpatient antimicrobial therapy (virtually and in person)

- involvement in MDTs including (not an exhaustive list)

- bone and joint infections

- diabetic foot infections

- transplant

- AMS ward rounds

- endocarditis ward rounds.

In part, this could be attributed to the development of combined infection training and dual accreditation with ID. However, even before this initiative, the remits of the medical microbiologist and medical virologist had started to expand quite rapidly due to increased demand for infection expertise at MDTs and expansion of national mandates for control and management of infections, including management of sepsis.

In addition to this, advances in laboratory diagnostics have required clinicians to spend time evaluating and implementing more advanced testing platforms, sometimes within a fast time-scale, e.g. during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. There has been an increased demand for the provision of remote advice from secondary and primary care. Patients are living longer and many infections are complex. The effect of pathology transformation has resulted in many centres working with reduced numbers of staff to cover greater areas, stretching services even further.

The role of the medical microbiologist in preventing and managing AMR

Policies on AMR management

Public Health England’s ‘Start Smart then Focus’ initiative recommended that healthcare organisations should have a multidisciplinary antimicrobial management group.5 There also need to be local organisational antimicrobial policies for commonly encountered infections, plus more specialised policies for specialist infections (e.g. ophthalmic infections, neurosurgical infections, etc). Development of these is commonly led by a medical microbiologist, as local resistance patterns need to be considered and liaison with colleagues in other specialties is required.

Data on prescribing needs to be collected, reviewed and discussed at a local level in accordance with Criterion 9 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008: Code of practice on the prevention and control of infections and related guidance (2022).6 In addition, medical microbiologists are required to be part of a ‘ward-focused antimicrobial team’, reviewing all antimicrobial prescriptions.

Overseeing AMS

Medical microbiologists are often the first port of call for queries from clinicians regarding the best antimicrobial to use for common and complicated infections. They undertake regular ward rounds in intensive care; many centres also undertake ward rounds for other specialties, overseeing AMS. Medical virologists also provide stewardship for more specialised antivirals.

While these initiatives undoubtedly help optimise patient safety and management of their current infection, as well as good AMS, they are extremely resource-intensive. In the current climate of workforce shortages, they present very real challenges to the infection specialties. The UK is not alone in diagnostic and AMS workforce challenges. Reports from the United States and Canada have cited similar challenges, which became evident during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.7,8 Burnout was also higher than pre-pandemic levels, which contributes to workforce shortages.

Impact of COVID-19 on AMS and AMR

The recent COVID-19 pandemic demonstrated how important it is to always maintain good AMS, even in the face of unprecedented pressure on healthcare services. Data from the UK surveillance programmes for rates of Gram-negative bacteraemia, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteraemia, methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) bacteraemia and C. difficile infections (CDI) shows that the pandemic had differing impacts on the rates and times of these infections.10

During the period April 2020 to March 2021, with lockdowns and 2 major COVID-19 peaks in the UK, reported rates of all community bloodstream infections and CDI declined.10 Most hospital onset cases of CDI and bacteraemias also decreased. However, hospital-onset cases of Klebsiella spp and Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemias increased, along with pneumonia due to MRSA, Klebsiella spp and P. aeruginosa. The third wave of COVID saw most infections return to pre-pandemic levels. The exceptions were E. coli and MRSA; there were also higher hospital-onset levels of CDI infections, Klebsiella spp and P. aeruginosa bacteraemia, compared to the pre-pandemic levels.10

It is challenging to make sense of this, given the range of interventions and consequences of the pandemic, including reduced elective hospital admissions and social distancing. Interventions changed at different stages of the pandemic, which may have influenced rates of different infections.

Following COVID-19 guidance

However, antimicrobial guidelines were changed in the context of COVID-19. The National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) issued rapid antimicrobial prescribing guidance, which included management of community-and hospital-acquired pneumonia.11

Andrews et al. (2021) reported that a third of organisations in the UK used these NICE guidelines to update their local antimicrobial guidelines for community- and hospital-acquired pneumonia.12 They found that 64% of hospitals reported a reduction in AMS activities due to COVID-19. Rates of usage of antimicrobials in hospitals rapidly increased in March–April 2020. There was a reduction in community antimicrobial prescribing, possibly due to lockdowns reducing general practice activity. However, in both primary and secondary care, prescriptions of broad-spectrum antibiotics and antibiotics for respiratory infections increased during the early months of the pandemic, despite overall volumes of antibiotic use decreasing.

It is possible that the rise in some healthcare-onset COVID-19 infections were related in part to a lack of AMS activity, although it is equally likely that there were challenges with maintaining good practices with regards to infection prevention and control.

Challenges facing AMS

AMS workforce

Although COVID-19 has not completely gone away, there is now restoration of normal activity. This has undoubtedly caused pressure on an already understaffed workforce within the NHS, including medical microbiology. How, then, can microbiologists achieve the ambitions of the UKSHA’s 3-year strategic plan?

Microbiologists and virologists still need to develop diagnostic, as well as clinical, services to ensure timely and accurate results. This can reduce the amount of empirical drug days, lowering the risk of developing AMR. Again, workforce shortages negatively impact on this. Newer diagnostics can reduce turnaround times and automation can reduce the potential for transcription and human errors. However, there is a paucity of newer diagnostics available and there may be challenges bringing in newer diagnostics due to procurement issues, even within pathology networks.

Implementing the hub and spoke model

Pathology configuration and development of networks may have many benefits, but also bring many challenges. One is how to ensure infection trainees at spoke hospitals maintain adequate laboratory experience and liaison – both for training purposes but also to develop an interest in medical microbiology and virology and recognise their important role for any infection specialist.

Another challenge is how to maintain relationships with clinical colleagues at all sites so that any AMS programme has their support. This may be a challenge in the context of workforce shortages and consultants being sequestered at the hub, resulting in sub-optimal services at the spoke hospitals. This is a particular challenge when the NHS workforce, in general, is exhausted and depleted on the back of the pandemic. How do we engage our colleagues in the fight against AMR?

Opportunities

These challenges also bring opportunities. COVID-19 showed us that, with the right funding and removal of unnecessary bureaucracy, diagnostics can be safely developed at pace and made available to all, eliminating the postcode lottery that may exist for procurement. This needs to be very much a global initiative, though, and requires greater collaboration and commitment to ensure parity for all.

Closer relationships with acute, emergency and respiratory medicine, as well as critical care services, can help to engender a culture of robust AMS and antimicrobial prescribing. Meanwhile, the development of the clinical scientist role has been very much welcomed and has benefited many departments. Encouraging more biomedical scientists to take up clinical liaison roles via the various pathways available to them will mean an increase in the number of laboratory-based specialists who can also undertake AMS.

Building an infection service with a greater skill mix of medical and biomedical staff, as well as involving allied specialties such as those in medicine and critical care, means we can develop AMS teams at a local departmental level with oversight from medical microbiologists and virologists. This can also enable the development of more educational programmes within secondary and primary care and the community, which could help reduce the burden of inappropriate prescribing.

There remains a need to increase national training numbers in infection and to better acknowledge the vast remit of microbiologists and virologists, and staff departments accordingly. The College has collaborated with the BIA to provide guidance on the allocation of programmed activities for key roles, such as AMS and infection prevention and control, which could help inform workforce planning within infection services.13

Conclusion

AMR remains a huge global threat. Good AMS is imperative; however, in the face of significant workforce shortages in the infection specialties, this remains a challenge to overcome. There is a pressing need to address the shortages in workforce and diagnostic capability both within the UK and worldwide.