Haemovigilance, which emerged in the 1990s, is defined as surveillance procedures that cover the whole transfusion chain from donation of blood, processing into components, through to follow-up of recipients. The intention of haemovigilance is to collect and assess information on unexpected or undesirable effects resulting from the therapeutic use of labile blood components and to prevent their occurrence or recurrence.1

Safer transfusion with haemovigilance data

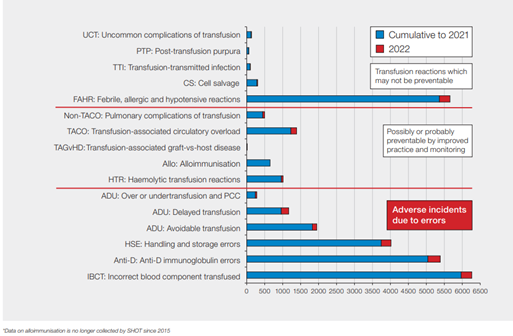

Since its inception in 1996, the UK haemovigilance scheme, Serious Hazards of Transfusion (SHOT), has accumulated more than 25 years of data on adverse reactions and events. In the early years, as a result of the collected data, measures were successfully introduced that reduced the risk of reactions due to transfusion-related acute lung injury and bacterial transmission.2 However, although some reactions cannot be prevented, the most common reported events (more than 80%) continue to relate to errors in transfusion practice (see Figure 1).3

It is encouraging to see high levels of haemovigilance reporting in the UK, which indicates a good reporting culture with an openness to share the learning when incidents occur. In the first year of SHOT reporting in 1996–1997, when reporting was voluntary, a total of 169 reports were submitted from 94 out of 424 (22%) eligible hospitals.4

Participation, now professionally mandated, sequentially increased and has been greater than 99% for many years.

In 2021, for the first time, all UK NHS Trusts and Health Boards involved in transfusions submitted reports.5 The high level of participation most likely relates to the fact that reports are confidential and anonymised, and organisations are provided with clear recommendations for improved practice.

Clinical impact of haemovigilance

Haemovigilance reporting helps inform and facilitate improvements in patient safety. The main causes of death related to transfusion in recent years have been transfusion-associated circulatory overload, ABO-incompatible (ABO-i) transfusion and delayed transfusions. Some of these should be preventable.

ABO-incompatible red cell transfusions

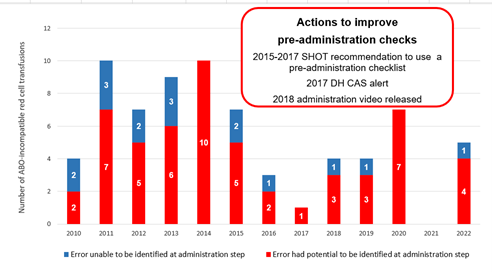

In the first 10 years of SHOT reporting (1996–2005), there were 15 deaths due to ABO-i red cell transfusions, but this reduced to 7 over the next 17 years (2006 to 2022). Key factors that influenced this were the introduction of the Blood Safety and Quality Regulations 20056 and the introduction of transfusion training and competency assessments.7

Near-miss reporting, where errors were detected before transfusion, has proved to be very educational. There are about 100 times more potential ABO-i cases than actual events, which are mainly due to detected wrong blood in tube errors (where the details on the tube are not those of the patient whose blood is in the tube).

Over the last 7 years, there were 24 ABO-i cases, but 2,118 near misses. The majority of ABO-i cases (55 out of 71, 77.5%) over the last 13 years could have been detected at the bedside if the final checks had been completed correctly (Figure 2).

Wrong blood in tube results from 2 main errors: failure to correctly identify the patient at the time of phlebotomy and labelling the sample away from the patient. These 2 errors were identified in the first SHOT report but remain common. Despite the Chief Medical Officer’s letter recommending mandatory use of a bedside checklist (CEM/CMO/2017/005, 2017),8 ABO-i cases still occur, with 2 preventable deaths in 2022.

Assumptions are dangerous. Inadvertent transfusion of ABOi blood components is considered wholly preventable; organisations should have processes in place to ensure that it does not happen. However, the failure to reduce the overall error rate remains a challenge.

Transfusion reactions

Febrile, allergic or hypotensive transfusion reactions and pulmonary complications continue to account for most cases with major morbidity. There are challenges with appropriate categorisation and management of transfusion reactions, as well as suboptimal management of acute transfusion reactions, particularly the continuing inappropriate use of antihistamines and/or steroids to treat febrile reactions. Certain reactions, such as hyperhaemolysis and cell-salvage-related events, are under-reported to SHOT. These are being addressed.

Some transfusion reactions cannot be prevented (e.g. acute febrile or allergic reactions) but others have been reduced as a result of changes introduced to donation (e.g. transfusion-related acute lung injury, transmission of infection). The risk of transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) can be reduced by including a risk assessment as part of the decision to transfuse, as recommended in the 2015 Annual SHOT Report.

Despite this, TACO continues to be one of the leading causes of transfusion-related deaths, with increasing numbers of reported cases and TACO related deaths year on year.9 Non-bleeding adult patients with severe chronic anaemia are particularly vulnerable to TACO, even in the absence of additional risk factors and comorbidities known to predispose to TACO. Inappropriate and avoidable transfusions, especially in patients with haematinic deficiencies, continue to be reported to SHOT.

Delays in transfusion

Delays in provision of red cells and other blood components in haemorrhage or cases of severe anaemia are preventable. Recognising the urgent need for blood components may be challenging where blood loss is not obvious, such as gastrointestinal bleeding and rapid fall in haemoglobin in severe cases of autoimmune haemolytic anaemia.

Laboratories should have clear processes for providing best match red cells using concessionary release in complex cases, including for patients with atypical red cell antibodies. A national patient safety alert in 2009 first identified the dangers of delays and recommended improvement actions.

Despite this, SHOT data continues to demonstrate deficiencies in processes, culminating in a further national patient safety alert in 2022 that mandated further improvements, including adding major haemorrhage drills, simulations and debriefs, into regular staff training activities for both clinical and laboratory teams.10

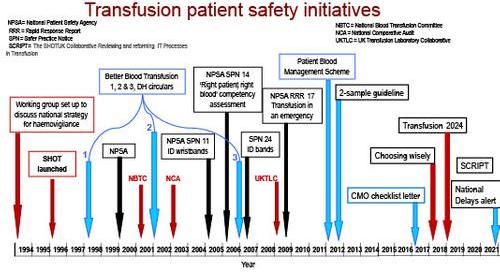

Numerous transfusion safety initiatives have been introduced in the UK since 1994 (Figure 3); while these have facilitated key changes, issues in staffing, poor IT and workload continue to threaten safety. These need to be addressed urgently.

Pathways to successful haemovigilance

The important role of information systems

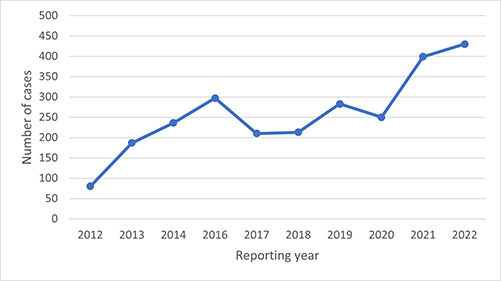

The number of cases reported to SHOT involving IT systems has risen dramatically over the last decade (Figure 4). IT can be an effective barrier to error if configured and used correctly. SHOT has recommended use of IT systems, both in the laboratory and clinical areas, to support safe transfusion since 2018.11

In response to the rising number of IT-related errors, in 2019 the SHOT UK Collaborative Reviewing and reforming IT Processes in Transfusion (SCRIPT) group was set up with the aim of enhancing transfusion safety through improved IT systems and practices. In 2021, SCRIPT completed a survey of the current state of transfusion-related IT in UK hospitals.

The results of this survey noted financial and resource challenges with upgrading laboratory information management systems (LIMS), deficiencies in LIMS functionality to support safe transfusion practice and lack of transfusion IT expertise. Electronic blood management systems (EBMS) support safe administration of blood components,12 but the SCRIPT survey noted only 57/97 (58.8%) respondents had these systems and just 17/57 (29.8%) of those were full vein-to-vein systems. EBMS, with effective LIMS, supports remote issue of red cells, providing a safe and costeffective process for rapid access to compatible red cells,13 yet just 7/57 (12.3%) of respondents to the SCRIPT survey were able to provide this service.

The inexorable march of electronic patient record systems and other electronic clinical systems into healthcare provides an opportunity for interoperability and electronic clinical decision support that can be harnessed to improve patient safety in transfusion. Many useful resources, including all the surveys mentioned here, are available on the SCRIPT webpage, which are designed to support implementation of transfusion IT systems.

Organisation and management of the transfusion service

Challenges continue with transfusion IT implementation, including finance, staffing, local expertise, functionality, interoperability and engagement with suppliers and hospital management. These need to be addressed nationally to ensure that systems are accessible to all and fit for the future to support transfusion safety.

The NHS is facing extraordinary challenges with financial, resourcing and staffing constraints and an ever-increasing workload. Safety II approaches to reconcile work-as-imagined and work-as-done are needed to create robust and resilient healthcare systems.14 SHOT data continues to reflect the ongoing demands, from staff shortages, difficulties in staff recruitment and retention, and poor system designs that impact on transfusion safety.15

There is a growing need to acknowledge the impact of human behaviour and performance on transfusion practice by reducing the emphasis on blame from individuals and focusing on improving systems to support safe practice.16 Applying human factor principles to incident investigation, system design, patient safety and quality improvement practices supports a cohesive, evidence-based and coherent approach to safety and quality of care.

These improvements can be achieved through a ‘systems thinking’ approach, using the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) framework.17 SEIPS provides a systematic methodology to improve the understanding of current work methods, foresee system behaviour and design adjustments to improve related functioning.

Engaging patients and the workforce in transfusion safety

SHOT recognises the key role patients play in promoting transfusion safety and has promoted the engagement of patients, their families and carers as safety partners, helping to co-create better systems with enhanced safety in healthcare.

Encouraging a people-centred healthcare system with an engaged workforce committed to patient safety will reduce near-miss events and errors.5

SHOT promotes a just learning safety culture by encouraging open and transparent reporting and demonstrating the benefits of this approach.2

A culture of shared learning through active collaboration and participation with all stakeholders and the promotion of a safety reporting culture within those associations is crucial for haemovigilance to function optimally.

Conclusions and future outlook

Data from SHOT helps to identify the gaps in clinical and laboratory practices that threaten transfusion safety in the UK. SHOT makes recommendations for improvement; however, there continue to be challenges in the effective implementation of these. NHS Trusts and Health Boards must use intelligence from all patient safety data, including national haemovigilance data, to inform changes in healthcare systems, policies and practices.

The lessons learned must be embedded to truly improve patient safety. System-level changes are needed to ensure that healthcare is a robust, safe and effective learning system with feedback loops. Healthcare leaders and management must ensure that staff have access to the correct IT equipment that is fit for purpose. Adequate financial resources are critical for the safe and effective functioning of teams.