Origins of the Systematic Review Initiative

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the Systematic Review Initiative (SRI) in transfusion medicine. The SRI was created following a call by the NHS Executive in their Health Service Circular ‘Better Blood Transfusion’1 to develop the evidence base in the field of blood transfusion. Professors Mike Murphy, David Roberts and Brian McClelland answered this call and, with funding from the UK Blood Services, established the SRI in 2002.

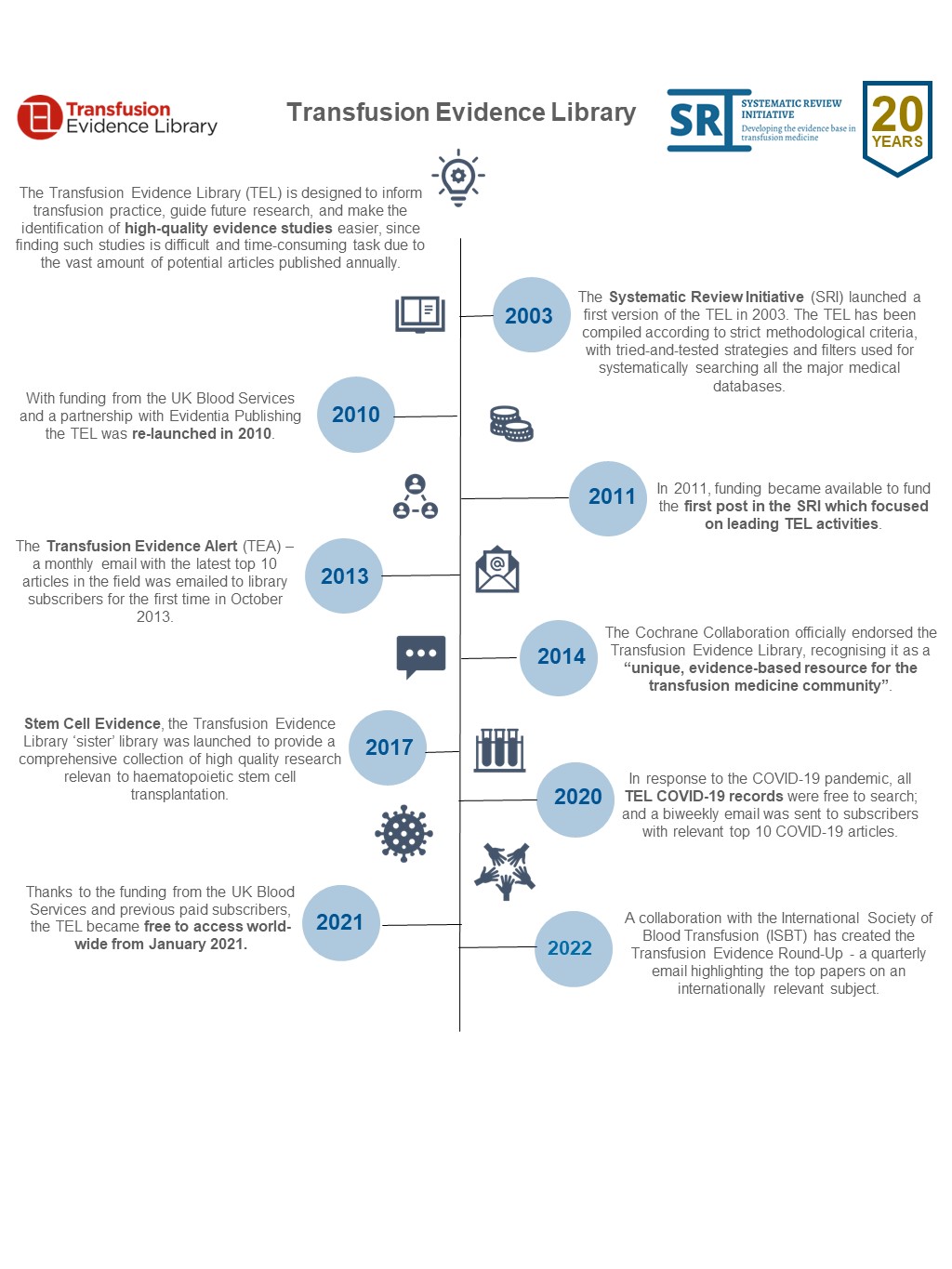

In October 2002, with expert methodological support from Professor Chris Hyde, a clinical research fellow and a junior systematic reviewer joined the SRI and began to explore how to address the SRI’s objective of increasing the evidence base for the practice of transfusion medicine. We began addressing this by undertaking and publishing systematic reviews, and, since 2003, through the development of our evidence libraries: Transfusion Evidence Library and Stem Cell Evidence.

The Systematic Review Initiative in 2022

The SRI has grown substantially in the last 20 years; the original clinical research fellow and junior systematic reviewer remain an integral part of the team as a principal investigator and SRI manager, respectively. The current team comprises three systematic reviewers, three information specialists, a manager and three principal investigators. Professor Lise Estcourt succeeded Professor Mike Murphy as director in November 2021.

The SRI is supported by an independent steering committee consisting of representatives from relevant professional bodies and clinical experts from the UK, France, Australia and North America. Over the years, we have welcomed many clinical fellows to the team who have completed transfusion medicine systematic reviews as part of their research studies; many have continued with their research as they have moved to senior clinical roles in UK and international health services.

Our systematic reviews

Our first systematic review, published in 2004, explored whether fresh frozen plasma was clinically effective.2

Since this first review, we have answered more than 70 systematic review questions and published over 240 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

Our reviews have covered the whole spectrum of transfusion medicine, although much of our recent focus has been on reviews that address the optimisation of blood component usage and interventions used as alternatives to transfusion.

We have been recipients of two National Institute for Health Research programme grants in the past eight years. The first focused on the safe and appropriate use of blood components and saw the completion of over 20 single intervention reviews in three years. The second used a complex statistical methodology, network meta-analysis, to compare in a single review many alternatives and adjuncts to transfusion to prevent and treat bleeding in people who are at risk of serious or life-threatening bleeding. These reviews in four clinical areas – cardiac, vascular surgery, trauma medicine and surgery, and elective orthopaedic surgery – will be published in the Cochrane Library through the course of 2022–2023.

Decisions on what systematic reviews to undertake and support in transfusion are made according to our priority checklist. This checklist is informed by a James Lind Alliance priority setting partnership we undertook between 2016 and 2018.3

The impact of our systematic reviews

The number of publications alone cannot be used to demonstrate the impact of research activities. Therefore, annually, we measure our impact on clinical practice, informing further research and influencing policy. In the last year, our systematic reviews have influenced 36 guidelines. In the last five years, we have influenced over 100 guidelines, including those published by the World Health Organization, the British Society of Haematology and the European Society of Anaesthesiology.

Case studies

An interesting and informative way to consider the impact of any research is to understand its story. Very often, our systematic reviews form part of a story of a clinical trial or a change in practice. Three such examples are presented here.

Supported change in blood donation guidelines In the UK in 2007, existing blood donors who developed non-insulin-dependent diabetes (NIDDM) or who were treated for hypertension were unable to donate blood, due to concerns for any detriment to their or a potential recipient’s health. Potential new donors were also not eligible to donate if they had either condition. However, such ineligibility to donate was considered a potential threat to the future sufficiency of the blood supply.4 We were commissioned, as part of a wider project on re-evaluating UK blood donor exclusion criteria, to conduct a systematic review of the evidence for excluding donors with treated hypertension and NIDDM controlled by oral hypoglycaemic drugs.

Decisions on what systematic reviews to undertake and support in transfusion are made according to our priority checklist.

The review identified 16 relevant papers. Although none directly addressed the review questions, all included papers provided contributory data and the findings were consistent. No study found any evidence of increased risk to blood donors with treated hypertension or raised systolic blood pressure up to 200 mmHg. We found very limited data relating to blood donation by diabetic subjects. This review supported changes to blood donor guidelines, which were implemented in 2008.

Risk of side effects highlighted over multiple updates

Cochrane reviews are updated at regular intervals. This process of adding new data to existing analyses can reveal interesting patterns in outcome data that would not be observed outside of such a setting. One example is our review of recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa) for the prevention and treatment of bleeding in patients without haemophilia (updated four times between 2007 to 2012).5 The benefits and risks of off-label use of rFVIIa in patients without haemophilia were contested.

At the latest update, our review contained 29 trials: 16 assessed prophylactic use of rFVIIa (1361 participants) and 13 assessed therapeutic use of rFVIIa (2,929 participants). There were mixed results in terms of the benefit (mortality, blood loss, use of red blood cell transfusion) of rFVIIa when compared to placebo. However, evidence for the risk of arterial events had increased over the three versions of the review and led to the conclusion in 2012 that ‘the results indicate increased risk of arterial events in patients receiving recombinant FVIIa. The use of recombinant FVIIa outside its current licensed indications should be restricted to clinical trials’.5

Since this first review, we have answered more than 70 systematic review questions and published over 240 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals.

From review to a clinical trial

Our systematic review on the use of platelet transfusions for the prevention of thrombocytopenic bleeding was first published in 2004 and has been updated multiple times.6 The premise for this review was, while the ready availability of platelet concentrates to treat bleeding had been lifesaving, there was still much debate about the use of prophylactic platelet transfusions to prevent thrombocytopenic bleeding.

The original review concluded that there was no reason to change clinical practice based on the evidence available. However, the unresolved uncertainty prompted one of the review authors to consider what further research could be undertaken to address the question about the use of prophylactic platelets. Working with other colleagues in NHS Blood and Transplant, the trial of prophylactic platelets study compared patients receiving platelet prophylaxis with those who did not. The trial, published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2013,7 supported the need for the continued use of platelet prophylaxis in patients with a haematological malignancy for reducing bleeding as compared to no prophylaxis.

The Transfusion Evidence Library

This year is also a milestone year for one of our evidence libraries, the Transfusion Evidence Library. It is 10 years since we formed a partnership with the digital publisher, Evidentia Publishing.

Together, we strive to achieve the aims of the Transfusion Evidence Library, which are to inform transfusion practice, guide future research and provide easy access to high-quality evidence studies.

The Transfusion Evidence Library is a database of systematic reviews and randomised controlled trials relevant to transfusion medicine. It is fully searchable, updated monthly and aims to be a key resource for medical practitioners, policymakers and researchers both in the UK and around the world.

It has a wide scope including donation practice, use of blood components, transfusion alternatives and the management of anaemia. The Transfusion Evidence Library is supported by a monthly evidence alert. The evidence alert highlights the top ten most recent papers added to the Transfusion Evidence Library in the last month and is sent to over 9,000 email addresses.

In 2014, the Cochrane Collaboration officially endorsed the Transfusion Evidence Library, recognising it as a ‘unique, evidence-based resource for the transfusion medicine community’. Last year we began a collaboration with the International Society of Blood Transfusion (ISBT) to create the new, quarterly Transfusion Evidence Round-Up. This highlights high-quality evidence studies, selected by ISBT members, about an internationally relevant subject in the field of transfusion medicine.

Summary

Over our first 20 years, we have undertaken over 70 systematic reviews, created two evidence libraries, and hosted and taught many clinical fellows. Our focus for the next few years is to continue what we have started. Specific projects in the next two years are to continue to build our relationship with ISBT, review our priority areas by updating our James Lind Alliance priority-setting partnership exercise and build our own website to have a central resource to disseminate our activities and improve our engagement with anyone interested in the practice of transfusion medicine.

Please follow us on Twitter: @sritransfusion, @evidencestemc, @transfusionlib.