I write this on 6 May – the day that the Nightingale Hospital London discharged its last patients and went into suspended animation in the sincere hope that it will not be needed again.

The initial call

It was only back in late March when I was contacted by the Medical Director, Dr Alan McGlennan, about setting up pathology support for the Nightingale Hospital. Only five minutes before I got his text I had heard the news about the first new field hospital to be set up to help the country deal with COVID-19 patients. It seemed surreal but of course I was happy to help if I could. After a short conversation I agreed to meet the other pathology workstream members on the following morning.

Setting the brief

The scale of a 100-acre hospital was daunting. Arriving early, I was able to join the intensive treatment unit (ITU) workstream meeting when the clinical model for the hospital was explained to the ITU consultants who, like me, had been cold called and asked to contribute if they could. This was fascinating. There were obvious concerns that simultaneously they were already heavily involved in the ‘surge’ of ITU capacity in their own Trusts. Then we were all reminded that this was to be a field hospital. Not all specialist services would be available on site and so patients with COVID-19 and known co-morbidities could not be safely treated there. For example, if a sickle cell patient with COVID-19 was admitted to the Nightingale London, how would the ITU team access appropriate advice? Therefore, the hospital needed strict acceptance criteria and all diagnostics at the hospital were to be highly protocol-driven.

‘If this turns out to be the biggest white elephant the UK has ever built, we will be delighted.’

Support from the Armed Forces

As well as biomedical scientists and pathology managers, I was pleased to see fellow College Council member Lt Col (Dr) Emma Hutley, the Defence Consultant Advisor for Pathology, in the pathology workstream. It was clear that the service had to be of equivalent quality to that anywhere else in the NHS. Emma, a consultant medical microbiologist with experience of setting up pathology services quickly in less than ideal circumstances, created a list of pathology tests as a potential repertoire (see Table 1). When this had been approved by the ITU Clinical Lead, we got started with planning the pathology service to meet the needs of the hospital’s intubated COVID-19 patients.

It quickly became clear to us that the pragmatic requirement was for point-of-care testing (POCT) in the wards with specimen reception and emergency blood transfusion available on site

Those of us who were brought up on episodes of M*A*S*H might have thought that the Armed Forces have fully equipped hospitals and laboratories in cold storage ready to be erected in a series of khaki tents when required. This impression was further supported by the nearby London City Airport having become RAF Nightingale with Chinook helicopters and C130 Hercules flying past and many in the conference centre dressed in military uniform. While the military do have rapidly deployable laboratories they are designed to support small, mobile military hospitals, not a 4,000 bed ITU as was being asked. The ability to set up robust, quality assured diagnostic pathology services quickly is a much more complicated process than simply struggling with a mallet and tent pegs. Electronically, the Nightingale London would be linked to the Cerner system at the Royal London Hospital as part of Barts Health NHS Trust since this hospital was the closest to the Excel centre. It quickly became clear to us that the pragmatic requirement was for point-of-care testing (POCT) in the wards with specimen reception and emergency blood transfusion available on site, with the wider repertoire of testing undertaken at the Royal London hospital in established laboratories where training programmes, quality systems, etc were already well established.

Mortuary provision

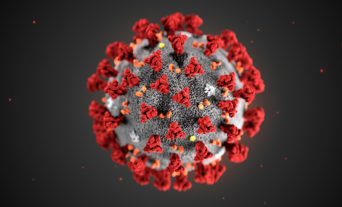

We were all aware from recent experience in China and Italy that, despite maximal treatment, some of the patients would sadly not survive. Autopsy histology images shared on social media by Dr Esther Youd from her practice showed clearly why that is the case. The CT images in which the lungs of the most severely ill COVID patients look exactly like the liver recall the red and grey hepatisation of yesteryear in the pneumonia pots in our pathology museums. For the first few days the pathology workstream was reassured that there was separate mortuary planning. On day three it became clear this workstream had yet to be set up. Within an hour of finding this out, I had recruited another College Council member Dr Mike Osborn, consultant histopathologist and President of the Association of Anatomical Pathology Technology, to set up the mortuary workstream (see Dr Matthew Clarke’s article).

Pathology services set up and POCT

The speed of building of the North and South ward areas, each able to house 2,000 patients, was awe-inspiring. However, in my opinion, the procurement, installation and verification of integrated point-of-care testing devices, building of a safe pathology reception and setting up of IT links with off-site hospital laboratories by my pathology workstream colleagues, clinical scientists and transfusion practitioners was equally impressive. By the time the first patients were admitted, the area initially marked just with black tape near the Eastern Entrance nine days previously had become a well-stocked, functioning, signposted and fully networked specimen reception with a blood fridge. Key to clinical needs were the blood gas analysers that needed to be put into place on the wards with staff trained to use them. Special mention needs to go to Jenny Lake who single-handedly set up, verified and quality assured the POCT gas analysers and implemented an induction training regimen within 48 hours.

Staffing for pathology services

But how did we staff these services? Pathology teams were needed to book in samples, provide on-site advice (and specimen rejection) and provide Code Red emergency blood transfusion support if needed for intubated patients. We were able to call on some experienced medical laboratory assistants from the Royal London hospital, but not wanting to take staff from stretched hospital services, we also looked for volunteers. My fellow RCPath Vice President Dr Tim Littlewood offered to contact Oxford medical students not yet deployed in the COVID effort who lived within travelling distance to the Excel site. Eleven medical students responded and were brought on board. Initially, we thought pathology staff would be asked to take swabs from ward staff for COVID-19 RT-PCR testing and this was the anticipation until a separate occupational health workstream was created with a drive-in staff testing facility at the Crick Institute.

Role of medical undergraduate volunteers

The clinical skills and knowledge of the students were invaluable, but more highly prized still was their ability to form an effective and efficient team. They organised their own rota to provide 24/7 cover seamlessly. Each medical student was on duty for eight-hour stretches. It was important to make the room adjacent to the pathology reception a little more pleasant for breaks during the long antisocial hours worked. Bringing in some wallpaper I had leftover from home and bright table cloths, with the help of two of the medical laboratory assistants, I was able to make this a fairly pleasant recreation room.

This was work experience like no other with long hours, last minute training sessions and heavy responsibilities. They were willing and able to take on new challenges. As gaps in ward staff inductions became apparent, they were happy to become part of the induction and training faculty providing POCT and blood transfusion training (see Dr Charlie McKechnie and Thomas Hanton’s article). In normal circumstances I would take new recruits out for dinner to help team building, but of course during COVID-19 lockdown this was not possible. I look forward to a reunion at some future point and when that happens dinner is on me!

Retired College Fellows

Anticipating digital connections, we had initially asked for volunteers from among the retired College Fellowship across the UK to support result reporting and clinical advice from home. I was hugely touched by the excellent response and the preparedness to countenance this remote form of return to clinical practice. It was anticipated that when patient volumes at the Nightingale London increased, the wonderfully supportive consultants from Barts Health NHS Trust would not be able cope with this additional workload on top of their already heavy clinical commitments. However, it became clear as April progressed that the ‘surge’ in NHS ITU capacity was ‘coping’ with the pandemic in the UK and the Nightingale London was not filled to anything like its potential capacity. So, these retired RCPath volunteers were never deployed.

Couriers rising to the challenge

A significant issue for all pathology services is specimen transport. We were extraordinarily fortunate that the TDL couriers who normally collect cervical screening samples from all over Greater London were at a loose end during the time of the pandemic. This was because throughout the UK women were either too scared of infection to attend their GP or found their GP practices were seeing only urgent cases. These couriers, who normally work within GP opening hours, were asked to volunteer to support the Nightingale London 24/7. I am very proud to say that the majority chose to support the new field hospital. These fully-trained couriers with appropriately equipped motorbikes worked 12-hour shifts to collect samples from the Nightingale centre, dropping off at the Royal London Hospital laboratories every 30 minutes throughout the hospital’s life. Along with the specimen reception staff, biomedical and clinical scientists and supervising consultants, these couriers ensured timely pathology services for the field hospital’s critically ill patients.

Final reflection

Despite the tragic circumstances, the last six weeks have been some of the most exciting and liberating of my time in pathology clinical management. The normal timescales for change and service development were abandoned as there was a real need for speed! It was a privilege to be part of this project, which was delivered with such momentum by a disparate group of people volunteering to work towards a common goal. The goal was to allow as many patients as possible to live to tell their own Nightingale tale.