In her profile, she explains her CRUK-funded research in state-of-the-art brain cancer detection technologies. She also emphasises the importance of her father’s advice for overcoming adversity.

How did you become an academic neuropathologist?

At medical school, I knew I wanted to be a consultant and pictured myself walking along corridors wearing a classy suit. I caught the investigative bug during my Experimental Pathology intercalated BSc and loved the lifestyle that pathology gave me. I thought ‘neuro’ sounded great and loved the research and teaching that neuropathology gave me more freedom to do.

My dad came to Britain in 1959 via train, boat and plane with £5 in his pocket. He had been teaching mathematics in Ethiopia, had paid off his family’s debts and wanted a better life. At the time, the UK government was inviting Commonwealth citizens because it needed workers, whereas the USA still had legal racial segregation in many states. As he was from Kerala, India, and was worried about racism in the USA, my dad chose to emigrate to the UK.

My mum moved from India to England later and I was born in Neasden, London, followed by my little sister, Anna. We experienced overt discrimination in those days: name-calling in the street, bricks thrown at our house, paint on our car and threatening phone calls.

As a teacher, my mum knew that education was a passport to a better life for me. She eventually became head teacher at Harlesden Primary in London, which was no mean feat for her in those days. My dad worked for British Airways for 20 years in the same role. His immediate line manager openly supported Enoch Powell and made sure that my dad never progressed in his career. My father died last year. He said his greatest achievement in his life was his two daughters. I miss him.

I got into Guy’s Medical School, where I did an intercalated BSc in Experimental Pathology. I earned a pathology training number, did an MD research degree and passed my Part 1 in General Pathology. Then I had a daughter, Sarina. I specialised in neuropathology, finally achieving my Part 2. Then I had a second daughter, Christina. After a locum consultant post in Cambridge for two years, I secured a substantive NHS consultant neuropathology post in Bristol.

Mine was not a traditional route or expected outcome, to be honest. I would say I have exceeded my original ambitions to be a consultant ... [but] needless to say, I have had multiple failures and rejections along the way, one or two of which nearly broke my spirit.

I kept doing research while I was an NHS consultant because it is my passion and, owing to this, I got an opportunity to join the University of Bristol as a Reader/Associate Professor. I was finally promoted to Professor of Neuropathology this year through my papers, grant funding, teaching and contributions to society.

What is neuropathology and who do you collaborate with?

We are a very small clinical subspecialty with approximately 65 neuropathology consultants supporting 27 regional neuroscience centres. We help patients with neurological diseases by providing diagnostic, prognostic and predictive information to guide treatment decisions. We work in small teams with our biomedical science and laboratory technician colleagues to diagnose specimens from patients with neurological disorders.

Most cases come from brain tumour patients. We make diagnoses while the patient is on the table to guide the neurosurgeon. We then refine our histologic diagnosis of the tumour specimen with molecular genetic data provided by geneticists. This informs the multidisciplinary team, which includes neurosurgeons, neuro-oncologists, nurse specialists, neuroradiologists and palliative care clinicians, who formulate the best treatment options to discuss with the patient.

We also diagnose neurological infections such as meningitis and inflammatory disorders detected in cerebrospinal fluid specimens from lumbar punctures. We identify muscle and nerve disorders by examining muscle and nerve biopsies sent from neurologists, rheumatologists and general medics, and diagnose eye disorders in some centres.

Importantly, we inform grieving families through examination of neurological post-mortem specimens (whole autopsies and fixed whole brains). We also give evidence to the coroner through forensic brain examinations and may act as expert witnesses in medicolegal cases.

What is the aim of your brain tumour research?

The aim of my research is to reduce the burden of brain cancer by identifying risk factors and biomarkers that will inform prevention, personalised diagnosis and treatment. I have a family member who had a brain tumour, so it is a personal as well as a professional passion.

My research spans epidemiology, biomarker research and translation to the clinic. Two examples include our early diagnosis Cancer Research UK (CRUK) project grant, for which I am a principal investigator, and the CRUK-funded GALA-BIDD trial in which I was a co-investigator.

Early diagnosis: CRUK-funded project grant

There is a pressing need for the discovery of new blood biomarkers for brain cancer and state-of the-art technology that allows for its sensitive detection.

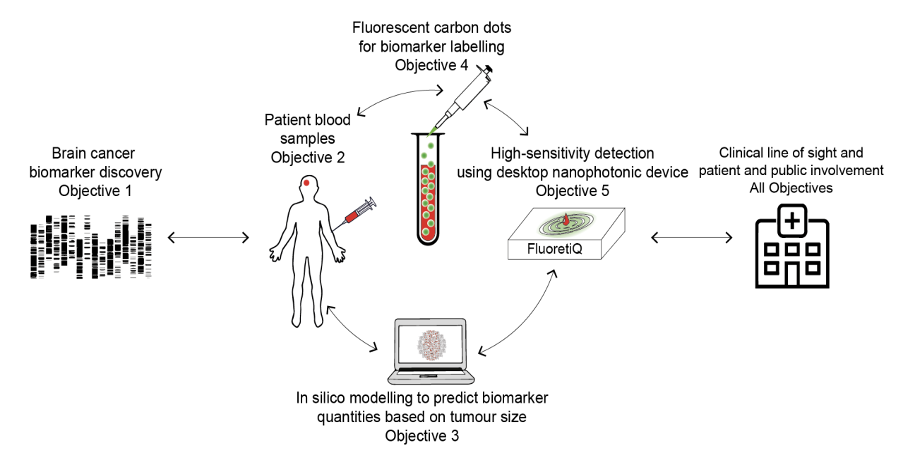

With this project we expect to:

- discover novel biomarkers, in addition to known markers such as glial fibrillary acidic protein, which will be used as a baseline

- develop a fluorescent nanoparticle that can label this marker in blood

- work with the startup FluoretiQ towards using cheap desktop nanophotonics for highsensitivity detection of nanoparticles.

Brain tumours reduce the life expectancy for an average patient by 20 years. In the UK in 2013, 38% of brain tumour patients visited their GP five times or more before diagnosis, which is partially because symptoms such as headache are not specific to brain tumours. We have shown that, although headache is strongly associated with brain cancer, the chance of a patient with headache having brain cancer is very low, meaning that many worried-well patients undergo negative MRI/CT scans to exclude diagnosis. Moreover, 62% of emergency presentations for cancer (between 2006 and 2008) were brain tumours, which may be large and inoperable. Early diagnosis is a top priority for the James Lind Alliance, as defined by the brain tumour neuro-oncology community.

A simple blood test performed by a GP in the clinic would aid decision-making and early diagnosis. This would revolutionise care by speeding up diagnosis, reducing costs and anxiety of unnecessary scans, and reducing the number of patients presenting with inoperable large brain tumours. Moreover, this test could be used as an early monitor of brain tumour recurrence. This work would be followed by a multicentre prospective cohort biomarker study to determine the efficacy of the test in a real-world setting.

By attaching a monoclonal antibody to a nanoparticle, different markers could be detected at lower detection levels (Figure 1). This is made possible by the fact that FluoretiQ is currently working on business models to deploy their high sensitivity test kits in clinical practices at a price point of £10 per test.

Figure 1. Overview of CRUK early diagnosis project grant using monoclonal antibodies conjugated to nanoparticles.

Intraoperative diagnosis: CRUK GALA-BIDD cohort study on 5-ALA

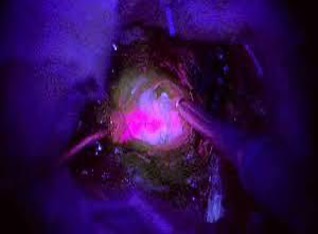

Intrinsic brain cancers (gliomas) are classified as low- and high-grade tumours. Correctly identifying high-grade gliomas during surgery can potentially improve removal and survival. Gliolan, also known as 5-aminolevulinic acid or 5-ALA, can be safely taken orally prior to surgery, which enters gliomas in part through blood vessels with an abnormal blood–brain barrier.

Glioma cancer cells have reduced ferrochelatase activity that normally metabolises 5-ALA, resulting in accumulation of protoporphyrin IX, a fluorescence generating substance, in their mitochondria. This means that the neurosurgeon can turn down the lights in surgery, turn on the ultraviolet lights and visualise the high-grade glioma which glows pink – otherwise known as ‘pink drink’ (Figure 2).

I assessed samples on the trial study on 5-ALA. The great news is that 5-ALA is now NICE approved and is given to all UK patients with suspected high-grade glioma.

What advice would you give to an aspiring academic pathologist?

When I was young, my dad told me the legend of the Scottish king, Robert the Bruce, who had been defeated in battle by the English six times and fled from the battlefield to hide in a cave. In the cave, he watched a tiny spider patiently build its web over and over again, after every time it was blown away. The spider’s persistence inspired the king to go back into battle and achieve victory. My dad’s words helped me through several hard times later in life. Essentially, he was telling me to 'never give up'. Keep spinning your dreams.

Mine was not a traditional route or expected outcome, to be honest. I would say I have exceeded my original ambitions to be a consultant, although I should add that I still cannot afford a Chanel suit. Needless to say, I have had multiple failures and rejections along the way, one or two of which nearly broke my spirit.

Get research experience early on in your career to see if you like it. First of all, try to help with any paper as a co-author and then move quickly from case reports to case series, which I believe are more valuable. Also, I would certainly advise doing a PhD rather than the MD. I had funding for a PhD but was advised to do an MD by my academic doubters. I would build your research on your clinical expertise and then collaborate outside your specialty. Do not do good work in silence – let your supervisors know. When self-doubt creeps in, channel Beyoncé and smile.