Do you have ‘wicked’ problems in your department? Have your attempts to change things become blocked or failed to stick? This article provides a wonderful trailer for the College’s first CQI Awareness Month in May 2019.

Background: a brief history of CQI in pathology

The NHS has increasingly recognised the importance of continuous quality improvement (CQI) since the mid-1990s. It has adopted ‘lean’, the basis of the world-renowned Toyota Production System, as its chosen route to achieve this. There is now generally strong awareness of CQI in frontline primary and secondary healthcare settings, even if genuine culture change remains limited.

It is puzzling why pathology is lagging behind the overall healthcare service. NHS pathology laboratories have a strong tradition of rigorous quality assurance and audit, a generally positive track record of innovation and a good understanding of research methods. Consequently, it would seem to be straightforward to incorporate CQI – which includes elements of all of these – into everyday practice. To build CQI capability, the National Pathology Service Improvement programme ,funded by NHS England from 2005 to 2012, invested more than £60m to support CQI initiatives at 15 pilot sites. In the devolved nations, initiatives to promote CQI have been more holistically directed at hospitals and/or health boards, rather than specifically at pathology.

A suite of extremely useful guidance, tools, exemplars and other resources was published during the years of the National Pathology Service Improvement programme, but the impact has been limited. Most of the pilot sites applied the funds to local projects, learning and applying lean methodology under external direction but without any culture change. These projects remain as stand-alone successes or have gradually unravelled. A second, smaller group of pilot sites engaged more actively, developing local lean champions. These projects have lasted better and undertaken additional CQI initiatives, but quality improvement remains ad hoc and is not done as part of routine work. In the third and smallest group, the investment was seen as an opportunity to take ownership of ‘lean’. The initial projects have had sustained benefit and CQI is now a regular feature of ‘usual’ work. Only in the third group has there been any significant culture change to embracing CQI.

In the absence of formal analysis, the quality of clinical and scientific leadership at the pilot sites has been cited as a key factor determining the longer-term outcome of the Pathology Service Improvement interventions. NHS England subsequently invested significantly in leadership development through programmes offered to senior pathologists from 2011 to 2016. These highly regarded programmes engaged approximately 130 medically trained pathologists, clinical scientists and biomedical scientists. One or two individuals from most large hospital trusts in England have benefitted and many have gone on to take up local or national leadership roles. Still, one individual attempting to influence a department of several hundred is a tall order. There is still a large unmet need for CQI training and leadership skills development within pathology. Delivering either without the other is recognised at the highest levels within the NHS as not cost effective.

The nature of problems: are they ‘wicked’?

The challenge of implementing CQI in pathology lies only 20% in building knowledge of CQI methods. 40% sits in the realm of developing emotionally intelligent leadership behaviours to articulate vision, engage stakeholders and persist against adversity. The next 20% lies with less tangible aspects of leadership, such as skills to understand and navigate the organisations and systems through which health and social care are delivered.

The final 20% is reserved for the nature of the problem itself. Pathologists and scientists often don’t pay enough attention to the nature of problems, tending to look at them simplistically as being somewhere along a continuum from easy to difficult. But what is ‘difficult’?

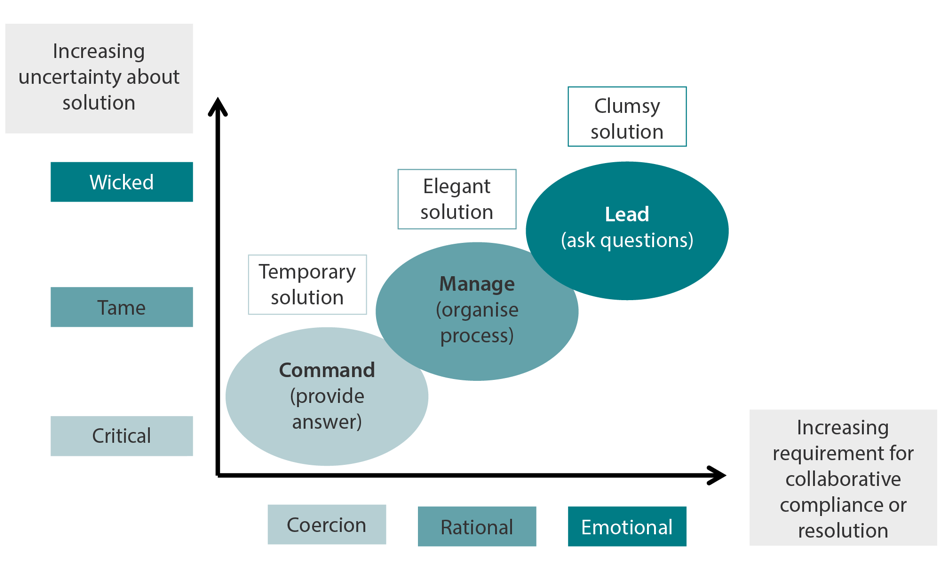

Rather than using a scale, problems can much more usefully be classified using typology from the work of Keith Grint1 and others who have studied problems and their solutions over many years (see Figure 1). Problems can be considered as:

- critical (emergencies)

- technical or tame (may be complicated)

- adaptive or ‘wicked’ (complex).

Figure 1: Keith Grint's typology classification of problems

In a critical or emergency situation, a well-understood and often standardised solution is typically implemented rapidly to limit the damage and create safe conditions to begin to recover. Examples would be police, fire or ambulance responses to a 999 call. There is a very direct cause-and-effect relationship between the problem and the solution, without many steps between one and the other. The solution is often only temporary, and easily accepted as such by those involved because of the urgent nature of the problem. The appropriate style of leadership for critical problems is directive or commanding; the priority is to implement the solution as quickly as possible. These are very important and urgent problems but – at least in the immediate phase – they are ‘easy’ because there is usually one obvious and very well understood solution to deliver.

Technical problems are what we spend most of our time dealing with every day. They are typically easy, or at least logical, to define. Like critical problems, they have a direct relationship between cause and effect, although there may be a much longer pathway between the two. When the pathway is very long, the problem may appear complicated, but it is solved by rational application of technical knowledge and a stepwise approach. We often write standard operating procedures to capture the individual steps in such complicated processes, to ensure consistency. When we encounter an unknown step in a technical problem, the likelihood is that we have experience from similar problems that we can adapt. These problems are sometimes referred to as ‘tame’ because they are hardly problems at all – they are readily dealt with by rational management and the appropriate solutions are ‘elegant’.

An adaptive or wicked (or complex) problem, however, is completely different. It may be difficult to define clearly; its nature only emerges over time and often incompletely even then. There is no straightforward cause-and-effect relationship – there are too many contributing factors, too many competing stakeholders, and there is too much uncertainty about the potential solutions. True leadership comes into its own here. ‘Adaptive’ in style, with the leader(s) able to engage the hearts and minds of participants, rally them behind a compelling cause and keep everyone focused through many twists, turns and blind alleys until a co-created solution is reached. There is often no truly perfect solution to a wicked problem, just one that is good enough for now while further work is done to create the next steps. These are ‘clumsy’ solutions borne of the need to do something, rather than nothing, while accepting that perfection is not attainable.

Identifying wicked problems and implementing CQI

Keith Grint uses the analogy of the architect and the bricoleur to explain tame/wicked problems and elegant/clumsy solutions. An architect starts with a clean sheet of paper and, following their client’s brief as they understand it, designs the perfect building. What starts off perfect on paper then has to be realised, which takes time and the coordinated input of many contributors, each knowing how to achieve their little bit of the plan. But there is a long lag time during construction, unexpected extra costs, delays and compromises, and the final result may no longer be fit for purpose by the time it is realised.

In contrast, a bricoleur is someone who is something of a ‘jack of all trades’ – a house builder and decorator, with some practical design skills, too. You call them in to discuss the house you already live in, with all its imperfections, to undertake alterations that you think will make it perfect. As the work gets under way, you discover unexpected obstacles; work stops until these are overcome. While waiting, new ideas lead to changed plans and the work changes as a result. Through all of this, you continue to live in your house, moving in and out of different areas to accommodate the evolving work. When the bricoleur and their team leave, a photograph of the house would not closely resemble the picture you had in your mind at the outset, but the result is highly functional and unique for your needs.

Trying to solve a wicked problem as if it were a technical one, with an elegant solution, is doomed to failure. Recognising a problem from the outset as being wicked sets us off along a completely different pathway of creating solutions, incrementally and collaboratively, to emerging aspects of the problem that can’t be known at the start. This is the approach that will eventually succeed – imperfectly but functionally.

Pathologists and scientists tend to approach topics for CQI as technical problems, partly because that fits with how we have been trained to work in our spheres of clinical and scientific knowledge. One of the most useful steps we can take to address the challenge of embracing CQI in pathology is to become bricoleurs. We need to recognise that most of the problems we seek to improve, from seemingly small changes within our own departments to network-wide reconfiguration of service provision, are wicked problems for which we need clumsy solutions.

References for this article are available on our references pages.