Dean Jones and Martin Allix are part of the Forensic Pathology Unit at the Home Office. Dean was formerly a senior investigating officer for Hampshire Police, and Martin was a senior investigator and forensic manager in the Royal Military Police, Special Investigations Branch. In this article, they summarise the outcomes of research into decision-making processes at the initial scene of an unexpected death.

‘It is a capital mistake to theorise before you have all the evidence. It biases the judgment.' – Sherlock Holmes

Failure to properly assess the scene of a death can prevent the investigation processes from forensically determining a cause of death. In a previous report produced for the Forensic Scientific Regulator1 and as part of a doctoral thesis,2 Dean Jones and Martin Allix examined influences on decision-making processes of police officers attending scenes of sudden and unexpected death in England and Wales.

There were three parts to the research: an examination of homicide statistics and forensic post-mortem (PM) data, which showed inconsistency in decision-making between some police forces; a case study of 32 real deaths where Home Office Registered Pathologists (HORFP) took over a PM procedure after the police had decided that the case was not suspicious but a non-forensic histopathologist felt that it was; and focus group interviews with those involved in operational decision-making at scenes of sudden and unexpected death.

Evaluating causes of death

The research found that homicide cases may be missed through poor decision-making. The mindset of police officers may influence the decision to treat them as non-suspicious and not use the services of a HORFP to give an expert medical opinion. Several recommendations were implemented to address the quality of death investigations, including a national policy, training of frontline officers and supervisors, and a standard operating procedure.

Death investigation in England and Wales follows one of three pathways. The first and most common relates to those deaths anticipated due to ill health, where a doctor can issue a Medical Certificate of the Cause of Death (MCCD). If a doctor is unable to issue a certificate because they had not recently been treating the deceased or the death was unexpected, the case is referred to a coroner for investigation, often with police assistance. Where the initial police investigation determines the death is non-suspicious, the coroner will continue with the investigation and may appointment a non-forensic histopathologist to conduct a PM and assist with establishing the medical cause of death. In suspicious cases, the police will assume primacy for the investigation and a coroner (in consultation with the police) will appoint a HORFP to conduct the PM. Should the initial police investigation be flawed, and the death deemed non-suspicious, there will be no forensic examination of the body and a potential homicide could be missed.

Forensic evidence in PMs

The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcomes and Death (NCEPOD) found that many non-forensic PM examinations were inadequate;3 in 1971, the Brodrick report highlighted discrepancies between clinical and PM diagnoses.4 Although the NCEPOD study is over 15 years old, the Royal College of Pathologists advised that, if anything, the situation had worsened since 2006.5

There are examples of police relying on the findings of non-forensic or routine PM examinations, to filter for foul play. This could lead, at best, to forensic evidence being lost during the PM or, at worst, to homicides being missed.6 Where homicide is a possibility, a HORFP must be appointed.

The decision to treat a death as suspicious and ensure that there is an appropriate medical determination of death by a HORFP is critical to the investigation. This raises the question as to how many homicides may be missed by non-forensically qualified pathologists. Six themes were identified as a result of this study.

Although the system of homicide investigation in England and Wales appears robust, the assessment of the initial scene of a sudden and unexpected death was found to be variable...

Why do sudden or unexpected deaths go unnoticed?

The lack of a national police policy

Although policies and procedures for the investigation of known or suspected homicides are embedded in police practice, no national policy existed for dealing with the initial stages of a sudden death report. Research was undertaken by the Forensic Pathology Unit of the Home Office in consultation with police forces, the College of Policing, Chief Coroner, Coroners’ Society of England and Wales, Forensic Science Regulator and forensic pathologists. Two national sets of guidance were developed in 2018.7,8

The lack of training for officers attending sudden and unexpected death

No formal training was in place for dealing with reports of sudden death. This was highlighted to the College of Policing, which oversees the national curriculum for the training of new joiners to the police, as well as supervisors and crime investigation training, to hopefully improve the quality of decision-making at the scene.

The mindset of decision makers in the early stages of a sudden and unexpected death investigation

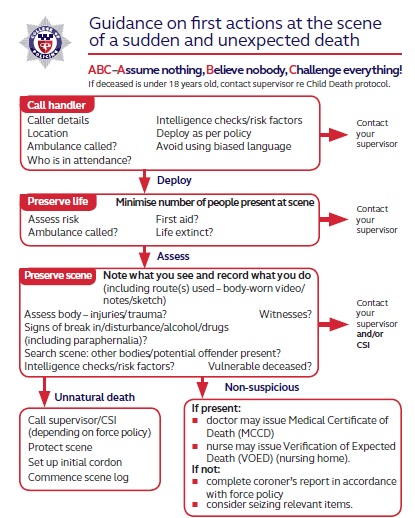

Evidence from focus groups and the 32 cases examined revealed that issues of bias such as ‘tunnel vision’ affected the decision-making of first attending police officers.9–13 A standard operating procedure was therefore produced to assist in decision-making (see Figure 1).

The use of other professionals in advising the police as to whether the case is suspicious or not The case studies identified the common practice of police calling a police doctor or force medical examiner to the scene to certify death. In four of the cases, the doctor assumed the overriding decision as to whether the death was suspicious or not. Junior officers appeared to readily accept the view of the doctor, without considering matters such as intelligence checks, missing property and the scene more generally. Such police doctors are not normally trained to interpret a scene. Their primary role is to take forensic samples from suspects and to assess prisoners’ fitness for detention. Guidance was issued, advising against calling a doctor to the scene, and where there is doubt as to whether life is extinct, an ambulance should be called. The research also revealed that some forces do not attend death scenes but leave their assessment to the paramedics who are not generally trained for this role.

The decision to treat a death as suspicious and ensure that there is an appropriate medical determination of death by a HORFP is critical to the investigation.

Financial considerations

Other evidence revealed that forensic PMs were not requested by the police owing to financial reasons. One force proposed that all suspicious deaths should attract a non-forensic PM in the first instance to act as a filter to determine foul play. Only then would a forensic pathologist take over the PM. There were also examples where police were reluctant to request a forensic PM owing to budgetary constraints (the difference in the fee payable to pathologists is significant; £96.80 for a ‘routine’ coroners’ case compared with almost £3,000 for a forensic case). However, a focus group of 22 senior investigating officers (SIOs) unanimously agreed that budgetary constraints were not an issue. Conversely, four focus groups of crime scene managers from across the country identified that in some police forces, finance was an issue.

Vulnerability of the deceased

Of the 32 cases examined, most involved a deceased who was in some way vulnerable. They were either very old or very young, or drug addicts or alcoholics. This raised the question about the level of investigation put into the circumstances of the death when there appeared to be an easily explainable first impression as to what caused it. Examples of this include:

- a police inspector deciding that a drowning in a bath was suicide because the premises was locked with no sign of a forced entry – the estranged partner was on bail for assaulting her and had a key

- a decision that a suspected paedophile had committed suicide by shooting himself with a shotgun, although the shotgun was never found

- an elderly lady died following an assault in a care home by another resident with dementia. No initial investigation took place due to the unlikelihood of securing a conviction.

- a young woman found dead in her flat where drugs paraphernalia were present was assumed to be a drugs overdose. The scene was cleared but it subsequently transpired she had been strangled.

- an alcoholic found dead with 66 blunt trauma injuries, initially thought to have been caused by a series of falls – two men were eventually convicted.

The adoption of a national policy on how to deal with death cases, along with a standard operating procedure and good quality training ... will hopefully improve the investigation by giving police officers the tools to make better judgements and decisions...

Conclusion

Although the system of homicide investigation in England and Wales appears robust, the assessment of the initial scene of a sudden and unexpected death was found to be variable, which could lead to potential homicides being overlooked. It cannot be estimated how many homicides are missed each year, but this study suggests that it is not unreasonable to assume that some will be.

The Forensic Pathology Unit is now routinely informed by HORFPs when they take over the conduct of a PM (approximately 100 such cases annually), and these are referred to the relevant police force to review decisions made at the scene. Poorly informed and biased decisions at the scene mean the investigation is denied the expert opinion of a HORFP, increasing the risk of a homicide being missed.

The adoption of a national policy on how to deal with death cases, along with a standard operating procedure and good quality training to frontline officers, will hopefully improve the investigation by giving police officers the tools to make better judgements and decisions – to make a fatal call and stop people getting away with murder.